The Hare

Let us sing of Hares, rich harvest of the hunt. The body is small and hairy, the ears are very long, small the head above, small the feet, the limbs unequal. The colour with which they are clothed varies; some are dark and dusky, which inhabit the black-soiled tilth; others are reddish-yellow, which live in red-coloured plains. Brightly flash their goodly orbs, their eyes armed with sleeplessness; for never do they slumber and admit sleep upon their eyelids, being afraid of the violence of wild beasts and the nimble wit of men, but they are wakeful in the night and indulge their desire. Unceasingly they yearn to mate and while the females are still pregnant they do not reject the lustful advances of the male, not even when they carry in the womb the swift arrow of fruitfulness. For this tribe, among all that the infinite earth breeds, is the most prolific. The one embryo comes forth from the mother's womb full-formed, while she carries one within her still hairless, and nourishes another half-formed, and has in her womb yet another — a formless foetus to look on. In succession she brings them forth and the shameless female never forgets her lust but fulfils all her desire and not even in the throes of birth does she refuse her mate.

—Oppian, Cynegetica, 3—

The Lepus Constellation

We will begin with the stars.

According to Hyginus' summary of Eratosthenes’ (the guy who measured the Earth's circumference) lost treatise on astral mythology, the Lepus constellation was appropriately placed by Hermes next to the great hunter Orion and his dog, from which it is fleeing, and is thus part of a hunting scene in the sky. Or at least this is the more popular theory.

Some learned men refute this by claiming that the noble hunter Orion wouldn’t be depicted hunting a lowly hare, rather he is facing off against the bull (Taurus constellation). I believe the great Orion is fully capable of doing both at once.1

But what is the reason why the hare is in the sky in the first place? Is it just to give Orion’s dogs something to do? Eratosthenes says that the following tale has been handed down through the ages:

In ancient times there were no hares on the island of Leros, but a young man of that land, who had a special fondness for the creature, brought in a pregnant female from abroad and took great care of her as she gave birth to her young. After she had done so, many of his fellow-citizens developed the same enthusiasm, and some acquiring hares through purchase, and some as gifts, they all began to rear them. And so, before long, hares came to be born in such huge numbers that the whole island is said to have been invaded by them. Since they were given nothing to eat, they attacked the corn-fields and devoured everything. Facing disaster as a result, being struck by famine, the whole body of citizens reached a common decision, and with great difficulty, so the story goes, they eventually drove the hares from the island. And afterwards, the image of a hare was thus placed in the heavens to remind people that, in this life, nothing is so desirable that one cannot subsequently derive more sorrow from it than joy.

This story echoes the many accounts from antiquity of ravages caused by out of control rabbit populations, especially on islands, of which I have already written in past articles (The Rabbit, Pliny’s Account of Nations Destroyed by Animals).

The Hare in Folktales

Hares were characterised by their timidity. Strabo mentions the following expression as an example for a hyperbole: ‘more timid than a Phrygian hare’ with both Phrygians and hares apparently sharing a reputation for being cowardly.2

Aelian lists hares, along with fawns, roe-deer, gazelles and antelopes as timorous creatures. Again, the association of timidity with hares is so strong that poets refer to them as 'cowerers' (πτῶκας).3

Aesop's fable of The Frightened Hares illustrates this well, with the hares coming to the conclusion that suicide is preferable to living perpetually under threat. Luckily on their way to the river they want to drown in they scare some frogs off and this makes them realise that even still there exists creatures who are scared of them so their situation is not so bad.

This tale is also present in the Buddhist Jataka. In the Roman de Renart, specifically the Trial of Renart, the hare Couard's anxiety theatrics cause him to have a fever for several days on the tomb of Renart's victim, Coupée the hen.

Staying on the topic of tales, in the West the rabbit and hare are often considered to have but a scanty allowance for brains, often being duped in Aesopic tales such as the Tortoise and the Hare. In french having the memory of a hare 'avoir une mémoire de lièvre/connil' means having a very short one. This is because it is said that the hare, in running, often forgets what it is running from, sometimes even running back to the very same burrow it had just been chased out of.

It is not so in Indian tales. In the Pancatantra the hare outwits both the arrogant and tyrannical lion, by convincing him that his reflection in the well is actually a rival lion, and the king of a herd of rampaging elephants, by claiming the Moon sent him to stop the elephants from harming those under the Moon's protection.

The Hare in Antiquity

In Ancient Egypt the hare was the symbol of the fertility goddess Unut, who was worshipped in Hermopolis (referred as Hare-Town in Egyptian texts). It goes without saying that hares are the animal symbol of fertility par excellence throughout human history and cultures.

As we will see, much has been written on this. For instance Pliny4 and Aelian5 both claim that hares are hermaphrodites and can reproduce on their own or, at the very least, that the male hare can get pregnant. Aelian goes so far as to claim that a hunter he trusts witnessed this himself. That same hunter adds that once he cut up the belly of a pregnant male hare and managed to revive the leverets within. I believe this as the narrator's tongue 'was a stranger to falsehoods and exaggeration'. Of course it could also just be that inguinal scent glands, which are located in the groin area, could have been mistaken for testes.

The Bible names the hare as one of the unclean animals as it is said that it chews the cud but does not part the hoof. The hare does not in fact chew the cud but is a hindgut fermenter like horses and rodents. The passage in question (Leviticus 11:5) was actually altered when King Ptolemy asked the sages to translate the Tanakh into Greek (this is the famous Septuagint, one of the oldest extant sources for the Bible). The Queen's name sounding similar to the Hebrew for hare, the sages did not want Ptolemy to think that she was being mocked and instead the Septuagint refers to the hare by an euphemism, δασύποδα, rough-footed. This is attested in the Talmud. 6

In the Talmud we also have the story of King Nebuchadnezzar eating a live rabbit or hare, I have talked about this in my article on the rabbit.7

Some Rabbis state that the garments God made for Adam and his wife (Genesis 3:21) were of hare hide. 8

The father of history Herodotus uses hares as an example for a weak animal who is hunted by all, thus has to reproduce prolifically while strong animals, such as lions (who he claims have single use wombs), bear few offspring. According to Herodotus the hare is the only animal who can conceive while already pregnant as its womb can contain young of any stage of development at once.9

This claim will later be echoed by Aristotle10 and Pliny.11

Superfetation is exceedingly rare in mammals, being known to only happen in certain species of bats and armadillos. Some cases in humans have been documented so it might be that it has been observed before in hares.

Herodotus later recounts12 an anecdote the Scythian campaign of Darius I where the Scythian army got distracted by a rabbit running between them and the Persian army. Every Scythian who saw the rabbit began to chase it, much to the offense of Darius, taking it as the Scythians mocking him. This bizarre anecdote does testify what was perhaps a custom or sport practiced by the Scythians. Such depictions have been found in their tombs.

The later Persian king Xerxes will have, some 30 years later, another strange encounter with a hare. As he is about to invade Greece a mare gives birth to a hare. Xerxes does not care. This is apparently an omen of his campaign failing. Another such omen is said to have happened too, a mule giving birth to a hermaphrodite. 13

A similar, but much spookier case, is said by Edward Topsell14 to have been witnessed by reputable men in the early 1500s. A mare brought forth a hare which bit its mother, killing her. While the men were watching the hare sucking the mare's blood it sprouted feathered wings and spoke up saying "O ye wretched mortal men weep and sigh, I go away!" at which words it flew away, never to be seen again.

Aristotle claims that the hare is the only animal which has hair in its mouth and underneath its paws15 and he praises the hare's rennet for fighting diarrhoea.16

Hare's rennet comes up quite often in classical works as a remedy for various poisons and diseases.

Furthermore it is said that hares cannot live on the island of Ithaca. If taken there it will be found dead, turned towards the point of the beach where it was landed.17

This is strange to me as in the Odyssey18 it is said that Odysseus' dog Argos hunted hares. Maybe they took him off the island? It might be worth noting that while it is generally accepted that Homer's Ithaca is indeed the modern day island of Ithaca, the possibility of it actually being Paliki has been recently proposed.

Perhaps Antiquity's most complete single account of hares comes again from Pliny.19 He claims that the hare has as many years as it has in its body openings for excrement and that there are numerous species of hares, including rabbits among them. In the Alps hares are white and eat snow, they turn a reddish colour when the snow melts. Nature treats hares as a sort of provision, a harmless and prolific source of food for all given its fertility. After all, the hare is the hairiest of creatures and hairy men are the most prone to lust.20

In some places hares have two livers but if they are moved to another location that second liver disappears.2122

Pliny dedicates an entire book on various remedies derived from animals and products from the hare (especially its rennet) make very, VERY, frequent appearances, and this European corpus of leporine remedies only ever grew over the years. Limiting myself to Pliny I will only bother listing the ones I found most amusing:

For tooth-ache: Either inject hare rennet into your ears or add ashes of its head into a dentifrice or use one of its bones to scarify your gums.23

Spitting blood? Try drinking hare rennet with Samian earth and myrtle-wine.24

Coughing at night? Reduce its dung to ashes and take it with wine in the evening.25

Need to get humours out of your lungs? Inhale hare fur smoke.26

Pain in the loins? Eat hare testes.27

Pain in the kidneys is cured by swallowing a hare's kidneys raw. (It is important that the kidneys do not touch the teeth).28

Intestinal hernia? Hare's dung, boiled with honey, to be taken daily in bean sized pieces.29

Urinary incontinence? Hare brains in wine. Grilled hare testes. Hare rennet taken with goose-grease and polenta. Pick whichever you prefer.30

Pesky thorns or splinters stuck inside you? You guessed it, hare rennet.31

This one is for the ladies, if you want male offspring then eat a hare's uterus (or the testes or the rennet) and take nine pellets of hare dung to keep your breasts perky. Men should drink the blood from a hare's foetus.32

If your infant child has diarrhoea spread some hare rennet on the nurses' breasts.33

The Cyranides, attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, add even more. My favourite is feeding teething children boiled hare brains.

Hare Hunting

So charming is the sight that to see a hare tracked, found, pursued and caught is enough to make any man forget his heart's desire.

—Xenophon, On Hunting, 5.33—

In a fair run she is seldom beaten by the hounds owing to her speed. Those that are caught are beaten in spite of their natural characteristics through meeting with an accident. Indeed, there is nothing in the world of equal size to match the hare as a piece of mechanism.

—Xenophon, On Hunting, 5.29—

It should come to no surprise that hares were hunted throughout the classical world for their meat. Thus it was often in the context of hunting that hares were discussed. Oppian points out that when hunting hares, hunters should make sure that they are chasing them downhill as the hare's forelegs are shorter than his hindlegs, thus putting it at a disadvantage downhill.34

Centuries later, the Physiologus will give this a Christian spin. Good Christians ought to run uphill towards virtues rather than downhill towards sins. Like the hare we are easier prey for the hunter/devil if we do the latter.

We have a pretty detailed account of contemporary hare hunting techniques in Xenophon's Cyropaedia which mentions dogs bred specifically for this task and making hares run from their hiding places into nets.35

In fact Varro goes so far as to warn us that dogs bought from a hunter are unlikely to keep to the flock and are more likely to run after hares instead.36

Training hounds on how to hunt hares is the focus of Xenophon work: On Hunting.

One interesting passage brings up the hare's extraordinary ability to proliferate, "at the same time she is rearing one litter, she produces another and she is pregnant." and it is sportsmanlike to leave the youngest hares to the Goddess Artemis.37

Xenophon also mentions that the smaller species of hares tend to inhabit and be abundant on islands as those tend to lack predators and hunters.38

Some speculations are also made as to the sight of the hare. Xenophon is of the opinion that it is poor for a slew of reasons ranging from anatomical to behavioural.39

He is wrong but I have to admit I was surprised such detailed speculations on the vision of animals were made back in 400BC.

What is true however is Pliny's observation that just like many human beings, hares are capable of sleeping with their eyes open.40

This is expanded on by Aelian whom experienced, true and honest hunters told that the hare sleeps with its body alone while its eyes continue to see.41

This seems to have eventually evolved into the belief that, as claimed by 13th century writer Bartholomaeus Anglicus, the hare needs his long ears to protect its eyes from flies and gnats while it is sleeping.42

Later still Topsell will write that the hare's eyelids are too short to cover their eyes. He claims that the Roman medical encyclopaedist Celsus calls the condition where a man cannot close his eyes fully 'Lagophthalmos' (Hare Eye), a term which is still in use today.43

Falconry can also be used to hunt hares but it seems to have only spread late in the Empire. We do have one testimony of the practice by Aelian. Indians are said to attach meat on tame hares and foxes to teach their eagles, ravens and kites to hunt them.44

Aelian likely knows this from Ctesias' fifth century BC work on India, which has sadly been lost. And according to him foxes employ yet another tactic to hunt hares. Given that a fox could never hope to keep up in pursuit of a hare it instead assures, through rousing noises, that the hare can never rest until it gives up from exhaustion. Slow and steady wins the race.45

The appetite for hares was clearly not shared by all ancient peoples as again the Jews think it's an abomination. Caesar claims that the inhabitant of the interior portion of Britain have a similar taboo around eating hares but still breed them for their amusement.46

Later English authors such as Anthony Burton will go so far as to attribute a melancholic quality to the hare's meat:

"Hare, a black meat, melancholy, and hard of digestion; it breeds incubus, often eaten, and causeth fearful dreams; so doth all venison, and is condemned by a jury of phisicians."

The Hare as Pet

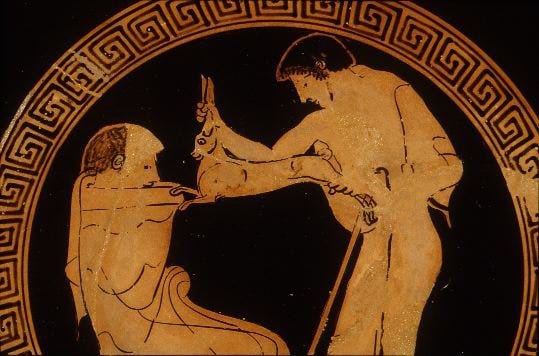

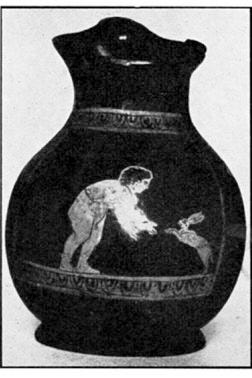

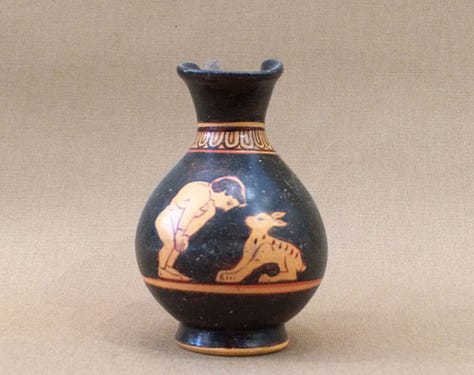

From art we know that hares were used as love-gifts and pets. Here's an excerpt from an article on the matter:47

The hare in art figures not only in scenes with children but with men and women as well. It was a very common love-gift from men to youths and from men to women. Sometimes, especially in vase-scenes, the animal is held in a very cruel manner, with seemingly little regard for the feelings of the pet-to‑be of the favored one. A Pentelic marble grave lekythos, in the National Museum at Athens, shows a youth who holds in his right hand a small hare grasped by its ears. As usual, choes furnish us very charming childhood scenes: a boy, with a white fillet in his hair, draws a small wagon on which his pet hare is sitting; again, a boy, wearing a band of amulets around his body, holds out his arms to a hare which is standing on its hind feet. On the lid of the sarcophagus of the emperor Balbinus one of the figures is that of a boy holding a hare in his arms.

We even have a Greek epigram from Meleager describing the life and death of such a pet bun:48

I was a swift-footed long-eared leveret, torn from ray mother's breast while yet a baby, and sweet Phaniŏn cherished and reared me in her bosom, feeding me on flowers of spring. No longer did I pine for my mother, but I died of surfeiting, fattened by too many banquets. Close to her couch she buried me so that ever in her dreams she might see my grave beside her bed.

Fast forward to the early 17th century writer Edward Topsell. He says that hares are almost impossible to tame as they are persuaded that all men are their enemies. Hares which are accustomed to humans can never be trained by their owner. He recounts that a tame hare in the castle of Mount-Pesal would regularly come and strike the dogs with its legs to provoke them to follow it.49

However it seems that Topsell missed John Caius' mention of a performing hare in De Canibus Britannicis:

"A hare (being a wilde and skippishe beast) was seene in England to the astonishment of the beholders, in the yeare of our Lorde God 1564, not onely dauncing in measure, but playing with his former feet uppon a tabbaret, and observing just number of strokes (as a practitioner in that arte) besides that nipping and pinching a dogge with his teeth and clawes, and cruelly thumping him with the force of his feete. This in no trumpery tale, (nor trifling toye) as I imagine, and therefore not unworthy to be reported, for I recken it a requitall of my travaile, not to drowne the seas of silence any speciall thing, wherein the providence and effectual working of nature is to be pondered."

Medieval Miscellany

When it comes to the hare medieval authors do not seem to have added much to the already rich lore inherited from their classical counterparts.

Saint Isidore claims that the 'lepus' comes from 'levipes' or swift-foot because of its speed.50

This opinion seems to come from the 2nd century BC author Lucius Aelius. We do not have his work but Varro quotes his etymological opinion and adds his own, that 'lepus' comes from an old Greek word, λέπορις (leporis).51

Gerald of Wales in his description of Ireland notes that the hares on the island, as with all other animals excluding humans, are smaller than their mainland counterparts.52

Thomas of Cantimpré53 teaches us that the weasel is said to enjoy playing with the hare, treacherously tiring it out before killing and eating it or, according to Topsell,54 drinking its blood while leaving its carcass to be devoured by other beasts. Also they change sex every year. Echoing the tragic epigram from earlier, hares fed inside quickly grow fat and die because the hare needs to burn fat through movement.

The Patron Saint of hares is Melangell of Powys, a 6th century Irish princess who vowed to remain celibate. To escape marriage she fled her father and lived in solitude away from any man for 15 years. One day the Prince of Powys was hunting hares and discovered the stunningly beautiful virgin deep in prayer, with the hare he had been hunting protected under her robe. Remarkably, the hunting dogs, usually relentless in pursuit, retreated and howled, refusing to attack the hare despite the hunters' attempts to incite them. Even more miraculous was when a huntsman tried to blow his horn, it adhered to his lips, preventing any sound.

Look at this picture I found

It is said that this Hare is fleeing the dog of Orion in the hunt; for since Orion was depicted as a hunter, as was right and proper, they also wanted to show what he was hunting, and so placed the hare in flight at his feet. Some say that it was Hermes who placed it there, and that it has been granted the capacity, shared by no other kind of four-footed beast, of being able to give birth to young while already being pregnant with others. But those who reject the preceding explanation say that it is hardly fitting that a hunter as mighty and renowned as Orion, whom we have already discussed in connection with the sign of the Scorpion, should be portrayed in pursuit of a hare. Callimachus too comes under reproach for having said, when writing in praise of Artemis, that she delighted in the blood of hares and used to hunt them. They have consequently pictured Orion as confronting the Bull.

Hyginus, De Astronomica

Our poet applies to rivers the epithet of ‘heaven-sent.’ And this not only to mountain torrents, but to all rivers alike, since they are all replenished by the showers. But even what is general becomes particular when it is bestowed on any object par excellence. Heaven-sent, when applied to a mountain torrent, means something else than when it is the epithet of the ever-flowing river; but the force of the term is doubly felt when attributed to the Nile. For as there are hyperboles of hyperboles, for instance, to be ‘lighter than the shadow of a cork,’ ‘more timid than a Phrygian hare,’‘to possess an estate shorter than a Lacedæmonian epistle;’ so excellence becomes more excellent, when the title of ‘heaven-sent’ is given to the Nile.

Strabo, Geography, 1.2.30

Here again I may as well speak of the peculiarities of animals. The sheep and the ass seem inclined to be sluggish; fawns, roe-deer, gazelles, antelopes, hares (which poets style 'cowerers') are timorous creatures. Timorous also are sparrows among birds, and the mullet among fishes.

Aelian, On Animals, 7.19

There are also numerous species of hares. Those in the Alps are white, and it is believed that, during the winter, they live upon snow for food; at all events, every year, as the snow melts, they acquire a reddish colour; it is, moreover, an animal which is capable of existing in the most severe climates. There is also a species of hare, in Spain, which is called the rabbit; it is extremely prolific, and produces famine in the Balearic islands, by destroying the harvests. The young ones, either when cut from out of the body of the mother, or taken from the breast, without having the entrails removed, are considered a most delicate food; they are then called laurices. It is a well-known fact, that the inhabitants of the Balearic islands begged of the late Emperor Augustus the aid of a number of soldiers, to prevent the too rapid increase of these animals. The ferret is greatly esteemed for its skill in catching them. It is thrown into the burrows, with their numerous outlets, which the rabbits form, and from which circumstance they derive their name, and as it drives them out, they are taken above. Archelaus informs us, that in the hare, the number of cavernous receptacles in the body for the excrements always equals that of its years; but still the numbers are sometimes found to differ. He says also, that the same individual possesses the characteristics of the two sexes, and that it becomes pregnant just as well without the aid of the male. It is a kind provision of Nature, in making animals which are both harmless and good for food, thus prolific. The hare, which is preyed upon by all other animals, is the only one, except the dasypus, which is capable of superfœtation; while the mother is suckling one of her young, she has another in the womb covered with hair, another without any covering at all, and another which is just beginning to be formed. Attempts have been made to form a kind of stuff of the hair of these animals; but it is not so soft as when attached to the skin, and, in consequence of the shortness of the hairs, soon falls to pieces.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 8.81

I have heard from one who is a hunter and a good man besides, the kind that would not tell a lie, a story which I believe to be true and shall therefore relate. For he used to maintain that even the male hare does in fact give birth and produce offspring and endure the birth-pangs and partake of both sexes. And he told me how it bears and rears its young ones, and how it brings perhaps two or three to birth; and he bore witness to this too, and then as the finishing touch to the whole story added the following. A male hare had been caught in a half-dead state, and its belly was enlarged, being pregnant. Now he admitted that it had been cut open and that its womb, containing three leverets, had been discovered. These, he said, which so far were undisturbed, were taken out and lay there like lifeless flesh, When however they were warmed by the sun and had spent some time slowly acquiring a little heat, they came to themselves and revived, and one of them, I suppose, stirred and looked up and presently put out its tongue as well and opened its mouth in its craving for nourishment. Accordingly some milk was brought, as was proper for such young creatures, and little by little they were reared up, to furnish (in my opinion) an astonishing proof of their birth by a male. I cannot prevail upon myself to doubt the story, the reason being that the narrator's tongue was a stranger to falsehoods and exaggeration.

Aelian, On Animals, 13.12

And in the list of unclean animals they wrote for him: The short-legged beast [tze’irat haraglayim]. And they did not write for him: “And the hare [arnevet]” (Leviticus 11:6), since the name of Ptolemy’s wife was Arnevet, so that he would not say: The Jews have mocked me and inserted my wife’s name in the Torah. Therefore, they did not refer to the hare by name, but by one of its characteristic features.

Megilah, 9b.3

“The Lord God made for Adam and for his wife garments of hide [or], and clothed them” (Genesis 3:21). In Rabbi Meir’s Torah, they found that “garments of or” was written. These are the garments of Adam the first man, that were similar to the common rue, broad at the bottom and narrow at the top. Rabbi Yitzḥak Ravya says: They were as smooth as a fingernail and as pretty as jewels. Rabbi Yitzḥak said: It was like the thin linen garments that come from Beit She’an. [And they were called] garments of hide because they adhered to the skin. Rabbi Elazar said: Goat hides. Rabbi Aivu said: Garments that cover the skin. Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi said: Hare hides. Rabbi Yosei bar Ḥanina said: Hides with their wool. Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish said: Radiant hides. And the firstborn sons would use them. Rabbi Shmuel bar Naḥman said: They were camel wool and hare wool. [And they were called] “garments of hide” because they were garments that come from hide.

Bereshit Rabbah, 20.12

The Arabians say that the entire world would be filled with these snakes if it were not for a certain phenomenon that happens to them , and which, I believe, also happens to vipers. And this phenomenon indeed makes sense: for divine providence in its wisdom created all creatures that are cowardly and that serve as food for others to reproduce in great numbers so as to assure that some would be left despite the constant consumption of them, while it has made sure that thosc animals which are brutal and aggressive predators reproduce very few off-spring. The hare, for example, is hunted by every kind of beast, bird, and man, and so reproduces prolifically. Of all animals, she is the only one that conceives while she is already pregnant; her womb can contain at the same time young that are furry, bare of fur, just recently formed, and still being conceived. That is the sort of pregnancy the hare has, but the lioness, since she is the strongest and boldest of animals, gives birth to only one offspring in her entire life, for when she gives birth she expels her womb along with her young. This happens because when the lion cub starts to move inside its mother, it lacerates the womb with claws that are sharper than those of any other beast, and as it grows, its scratches penetrate deeper and deeper, so that near the time of birth there is nothing at all of the womb left intact.

Herodotus, Histories, 3.108

Hares copulate in a rearward posture, as has been stated, for the animal is opisthuretic. They breed and bear at all seasons, superfoetate during pregnancy, and bear young every month. They do not give birth to their young ones all together at one time, but bring them forth at intervals over as many days as the circumstances of each case may require. The female is supplied with milk before parturition; and after bearing submits immediately to the male, and is capable of conception while suckling her young. The milk in consistency resembles sow’s milk. The young are born blind, as is the case with the greater part Of the fissipeds or toed animals.

Aristotle, History of Animals, 4.33

See Note 2

After the gifts had been sent to the Persians, the Scythians who had stayed behind deployed their infantry and cavalry in preparation to give battle to Darius. The Scythians were assembled in their positions when a hare darted into the space between the armies. Now every Scythian, when he saw the hare, began to chase it! Darius noticed that the Scythians were shouting and in disorder and asked what the uproar among his enemies was all about. When he learned that they were chasing a hare, he said to the men with whom he usually discussed everything, "These men look on us with such contempt! I now believe that Gobryas' interpretation of the gifts from the Scythians was correct. And now that I, too, finally see things his way, we must form a good plan to ensure that our return journey home will be a safe one." In response to this, Gobryas said, "Sire, the reputation alone of these men had led me to a nearly perfect awareness of how impossible they would be to deal with, but since I have come here myself, and have watched them mock us, I have gained an even more profound understanding of them.

Herodotus, Histories, 4.134

When all of them had crossed over and they were setting out on their journey, a great portent appeared to them. Xerxes paid no attention to it, however, although it was quite easy to interpret. A horse gave birth to a hare, which clearly symbolized the fact that Xerxes was about to lead an expedition against Hellas with the greatest pride and magnificence, but would return to the same place running for his life. Another portent had occurred earlier while he was still in Sardis; there a mule had given birth to a mule with two kinds of genitals, both male and female, with the male genitals above the female.

Herodotus, Histories, 7.57

Edward Topsell, History of Four Footed Beasts, p.214

The hare, or dasypod, is the only animal known to have hair inside its mouth and underneath its feet. Further, the so-called mousewhale instead of teeth has hairs in its mouth resembling pigs’ bristles.

Aristotle, History of Animals, 3.12

Rennet then consists of milk with an admixture of fire, which comes from the natural heat of the animal, as the milk is concocted. All ruminating animals produce rennet, and, of ambidentals, the hare. Rennet improves in quality the longer it is kept; and cow’s rennet, after being kept a good while, and also hare’s rennet, is good for diarrhoea, and the best of all rennet is that of the young deer.

Aristotle, History of Animals, 3.21

The hare cannot live in Ithaca if introduced there; in fact it will be found dead, turned towards the point of the beach where it was landed.

Aristotle, History of Animals, 8.28

Thus they spoke to one another. And a hound that lay there raised his head and pricked up his ears, Argos, the hound of Odysseus, of the steadfast heart, whom of old he had himself bred, but had no joy of him, for ere that he went to sacred Ilios. In days past the young men were wont to take the hound to hunt the wild goats, and deer, and hares; but now he lay neglected, his master gone, in the deep dung of mules and cattle, which lay in heaps before the doors, till the slaves of Odysseus should take it away to dung his wide lands. There lay the hound Argos, full of vermin; yet even now, when he marked Odysseus standing near, he wagged his tail and dropped both his ears, but nearer to his master he had no longer strength to move. Then Odysseus looked aside and wiped away a tear […]

Homer, Odyssey, 17.290

See Note 2

The dasypus has hair in the inside of the mouth even and under the feet, two features which Trogus has also attributed to the hare; from which the same author concludes that hairy men are the most prone to lust. The most hairy of all animals is the hare.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 11.94

The hares that are found in the vicinity of Briletum and Tharne, and in the Chersonnesus on the Propontis, have a double liver; but, what is very singular, if they are removed to another place, they will lose one of them.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 11.73

Theopompus reports that in the country of the Bisaltae [Macedonian tribe living on the west coast of the gulf of the Strymon] the hares have a double liver.

Aelian, On Animals, 5.27

For the cure of tooth-ache, hare's rennet is injected into the ear: the head also of that animal, reduced to ashes, is used in the form of a dentifrice, and, with the addition of nard, is a corrective of bad breath. Some persons, however, think it a better plan to mix the ashes of a mouse's head with the dentifrice. In the side of the hare there is a bone found, similar to a needle in appearance: for the cure of tooth-ache it is recommended to scarify the gums with this bone.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 28.49

Spitting of blood is cured by taking ashes of burnt deer's horns, or else a hare's rennet in drink, in doses of one-third of a denarius, with Samian earth and myrtle-wine. The dung of this last animal, reduced to ashes and taken in the evening, with wine, is good for coughs that are recurrent at night. The smoke, too, of a hare's fur, inhaled, has the effect of bringing off from the lungs such humours as are difficult to be discharged by expectoration.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 28.53

See Note 22

See Note 22

For pains in the loins and all other affections which require emollients, frictions with bears' grease should be used; or else ashes of stale boars' dung or swine's dung should be mixed with wine and given to the patients. The magicians, too, have added to this branch of medicine their own fanciful devices. In the first place of all, madness in he-goats, they say, may be effectually calmed by stroking the beard; and if the beard is cut off, the goat will never stray to another flock. To the above composition they add goats' dung, and recommend it to be held in the hollow of the hand, as hot as possible, a greased linen cloth being placed beneath, and care being taken to hold it in the right hand if the pain is on the left side, and in the left hand if the pain is on the right. They recommend also that the dung employed for this purpose should be taken up on the point of a needle made of copper. The mode of treatment is, for the patient to hold the mixture in his hand till the heat is felt to have penetrated to the loins, after which the hand is rubbed with a pounded leek, and the loins with the same dung annealed with honey. They prescribe also for the same malady the testes of a hare, to be eaten by the patient. In cases of sciatica they are for applying cow-dung warmed upon hot ashes in leaves: and for pains in the kidneys they recommend a hare's kidneys to be swallowed raw, or perhaps boiled, but without letting them be touched by the teeth. If a person carries about him the pastern-bone of a hare, he will never be troubled with pains in the bowels, they say.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 28.56

See Note 25

The ashes of a kid's thighs are said to be marvellously efficacious for intestinal hernia; as also hare's dung, boiled with honey, and taken daily in pieces the size of a bean; indeed, these remedies are said to have proved effectual in cases where a cure has been quite despaired of.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 28.58

The bladder of a wild boar, eaten roasted, acts as a check upon incontinence of urine; a similar effect being produced by the ashes of the feet of a wild boar or swine sprinkled in the drink; the ashes of a sow's bladder taken in drink; the bladder or lights of a kid; a hare's brains taken in wine; the testes of a male hare grilled; the rennet of that animal taken with goose-grease and polenta; or the kidneys of an ass, beaten up and taken in undiluted wine.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 28.60

Thorns and similar foreign substances are extracted from the body by using cats' dung, or that of she-goats, with wine; the rennet also of any kind of animal, that of the hare more particularly, with powdered frankincense and oil, or an equal quantity of mistletoe, or else with bee-glue.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 28.76

The hare, too, is remarkably useful for the complaints of females: the lights of that animal, dried and taken in drink, are beneficial to the uterus; the liver, taken in water with Samian earth, acts as an emmenagogue; and the rennet brings away the after-birth, due care being taken by the patient not to bathe the day before. Applied in wool as a pessary, with saffron and leek-juice, this last acts as an expellent upon the dead fœtus. It is a general opinion that the uterus of a hare, taken with the food, promotes the conception of male offspring, and that a similar effect is produced by using the testes and rennet of that animal. It is thought, too, that a leveret, taken from the uterus of its dam, is a restorative of fruitfulness to women who are otherwise past child-bearing. But it is the blood of a hare's fœtus that the magicians recommend males to drink: while for young girls they prescribe nine pellets of hare's dung, to ensure a durable firmness to the breasts. For a similar purpose, also, they apply hare's rennet with honey; and to prevent hairs from growing again when once removed, they use a liniment of hare's blood.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 28.77

A hare's rennet, applied to the breasts of the nurse, effectually prevents diarrhœa in the infant suckled by her.

Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 28.78

In hunting the swift-footed tribes of the Hare the hunter should run in front and head them off from upward-sloping rock or hill and with cunning prudence drive them downhill. For the moment that they see hounds and huntsmen they rush uphill; since they well know that their forelegs are shorter. Hence hills are easy for Hares — easy for Hares but difficult for mounted men. Moreover, the hunter should avoid much-trodden ways and the beaten track and pursue them in the tilled fields. For on the trodden way they are nimbler and light of foot and easily rush on. But on the ploughed land their feet are heavy in summer and in the winter season they carry a fatal shoe that reaches to the ankle.

Oppian, Cynegetica, 4

And again, to catch the hare—because he feeds in the night and hides in the daytime—you used to breed dogs that would find him out by the scent. And because he ran so fast, when he was found, you used to have other dogs trained to catch him by coursing. And in case he escaped even these, you used to find out the runs and the places where hares take refuge and may be caught, and there you would spread out your nets so as to be hardly visible, and the hare in his headlong flight would plunge into them and entangle himself. And lest he escape even from that, you used to station men to watch for what might happen and to pounce upon him suddenly from a place near by. And you yourself from behind shouting with a cry that kept right up with the hare would frighten him so that he would lose his wits and be taken; those in front, on the other hand, you had instructed to keep silent and made them lie concealed in ambush.

Xenophon, Cyropaedia, 1.6.40

You should be careful not to buy dogs from huntsmen or butchers — in the latter case because they are too sluggish to follow the flock, and in the other because if they see a hare or a stag they will follow it rather than the sheep. It is better, therefore, to buy from a shepherd a bitch which has been trained to follow sheep, or one that has had no training at all; for a dog forms a habit for anything very easily, and the attachment he forms for shepherds is more lasting than that he forms for sheep.

Varro, De Re Rustica, 2.9.5

The animal is so prolific that at the same time she is rearing one litter, she produces another and she is pregnant. The scent of the little leverets is stronger than that of the big ones; for while their limbs are still soft they drag the whole body on the ground. Sportsmen, however, leave the very young ones to the goddess. Yearlings go very fast in the first run, but then flag, being agile, but weak.

Xenophon, On Hunting, 5.13-14

There are two species of hare. The large are dark brown, and the white patch on the forehead is large; the smaller are chestnut, with a small white patch. The larger have spots round the scut, the smaller at the side of it. The eyes in the large species are blue, in the small grey. The black at the tip of the ear is broad in the one species, narrow in the other. The smaller are found in most of the islands, both desert and inhabited. They are more plentiful in the islands than on the mainland, for in the majority of these there are no foxes to attack and carry off the hares and their young; nor eagles, for they haunt big mountains rather than small, and the mountains in the islands, generally speaking, are rather small. Hunters seldom visit the desert islands, and there are few people in the inhabited ones, and most of them are not sportsmen; and if an island is consecrated, one may not even take dogs into it. Since, then, but few of the old hares and the leverets that they produce are exterminated by hunting, they are bound to be abundant.

Xenophon, On Hunting, 5.21-25

The sight of the hare is not keen for several reasons. The eyes are prominent; the lids are too small and do not give protection to the pupils; consequently the vision is weak and blurred. Added to this, though the animal spends much time asleep, it gets no benefit from that, so far as seeing goes. Its speed, too, accounts in no small degree for its dim sight. For it glances at an object and is past it in a flash, before realising its nature. And those terrors, the hounds, close behind them when they are pursued combine with these causes to rob them of their wits. The consequence is that the hare bumps against many obstacles unawares and plunges into the net. If she ran straight, she would seldom meet with this mishap. But instead of that she comes round and hugs the place where she was born and bred, and so is caught. In a fair run she is seldom beaten by the hounds owing to her speed. Those that are caught are beaten in spite of their natural characteristics through meeting with an accident. Indeed, there is nothing in the world of equal size to match the hare as a piece of mechanism.

Xenophon, On Hunting, 5.26-29

In addition to this, it is the fact that hares, as well as many human beings, can sleep with the eyes open, a thing which the Greeks express by the term χορυβαντιᾷν.

Pliny, Natural History, 11.54

It seems that the hare knows about winds and seasons, for it is a sagacious creature... During the winter it makes its bed in sunny spots, for it obviously likes to be warm and hates the cold. But in summertime it prefers a northern aspect, wishing to be cool. Its nostrils, like a sundial, mark the variation of the seasons. The hare does not close its eyes when sleeping: this advantage over other animals it alone enjoys and its eyelids are never overcome by slumber. They say that it sleeps with its body alone while it continues to see with its eyes. (I am only writing what experienced hunters say.) Its time for feeding is at night, which may be because it desires unfamiliar food, though I should say that it was for the sake of exercise, in order that, while refraining from sleep all this time and full of activity, it may improve its speed. But, it greatly likes to return to its home and loves every spot with which it is familiar. That, you see, is why it is generally caught, because it cannot endure to abandon its native haunts.

Aelian, On Animals, 13.13

The Hare is called Lepus, as it were Levipes, light foote, for hée runneth swiftly, and is called Lagos in Gréeke, for swiftnesse in running. And li. 12. Isidore sayth, that every swifte beast is fearefull and fighteth not, and hath no manner kinde of armour nor of wepon, but onely lightnesse of members and of lims, & is feeble of sight as other beasts be, that close not the eye lids in sléeping, and is better of hearing than of sight, namely when he reareth up the eares. His eares be full long and pliant, & that is néedefull for to defend the eyen, that be open, & not defended with covering, nor with heling to kéep them from gnats and flyes great & small, for against noyfull things, kinde giveth remedy to creatures, as Avicen[na] saieth. And therefore kinde giveth to the Hare lightnesse and pliantnesse of limmes, and swiftnesse of course and of running, to kéep him from houndes & other beasts that pursue him: and kind giveth him long eares, against gnats and flyes, that grieve oft and busiy his féeble eyen, as he saith: & kinde giveth much haire under his feete, that the haire of the féete maye defende the flesh thereof from hurting in running, & for he should by lyghtnesse thereof in no wise let the féete in running: and therfore Arist[otle] saith li. 3. that the Hares feete be hairie beneath, & that is seldome séene in other beasts. His hinder legs be longer than the former, and that is néedfull to reare the body when he flyeth: & when he runneth against an hil, he is harder to take, than when he runneth downward toward the valley, & that is for shortnes of the fore legs, for because of lownesse of the fore part of the body, hée falleth soone when he runneth downe the hill, and may not continue evenly his course and running, & for he séeth, that he shall fall when he runneth and flyeth downe a hill, he runneth therefore aside and aslont by the hill side, and reareth the former legs as he may, towarde the highnesse of the hills side, and ofte beguileth the hounds that him pursueth, and scapeth in that wise. And li. 8. ca. 55. Plini[us] speaketh of Hares and sayth, that many kindes be of Hares, for some are more in quantitie, with more great haire and rough, and more swifte of course and of running, than those that be called Cuniculi, and so héere this name Lepus, is the name of Hares and of Conies: for Conies be called Parvi Lepores, small Hares & féeble, & they dig the earth with their clawes, and make them bowers & dens under the earth, and dwell therein, and bring foorth many Rabets & multiply right much. And in some Woodes of Spain, be so many Conies, that somtime they wast and destroy corne in the fielde, by the which they cause hunger in the Countrey and lande: and Rabets are so loved in the Iland Balearitis, yt those Rabets be taken and eaten of men of the countrie, though the guts be unneth cleansed. And it followeth there, ye Archelaus the Author saith, that as manye dens as be in the increasing of the Conies, so many yeres they have of age. In the bodye are so many hoales, as the Conies have yeres. Therefore it is said that they gender without males, & have both sexes, male and female: therefore many men suppose, that the Conie gendereth and is gendered without male, as he sayth: and such Conies be so plenteous, and bring forth so much breede, that when they bring forth one Rabet or moe, anone she hath another in hir wombe, and is a profitable beast both to meate and to clothing, and to many maner medicines, for his ruenning helpeth agaynst venime, and stancheth the flixe of the wombe, his bloud abateth ache & smarting of eyen, as Plinius sayth, and Dioscorides also: and in no beast with téeth in either jawe, is ruenning found, but in the Hare, as Arist[otle] saith: and the elder the ruenning is, the better it is, as Plinius saith.

Bartholomaeus Anglicus, Liber de Proprietatibus Rerum, 18.67

Edward Topsell, History of Four Footed Beasts, p.208

This is the way in which the Indians hunt hares and foxes: they have no need of hounds for the chase, but they catch the young of eagles, Ravens, and Kites also, rear them, and teach them how to hunt. This is their method of instruction: to a tame hare or to a domesticated fox they attach a piece of meat, and then let them run; and having sent the birds in pursuit, they allow them to pick off the meat. The birds give chase at full speed, and if they catch the hare or the fox, they have the meat as a reward for the capture: it is for them a highly attractive bait. When therefore they have perfected the birds' skill at hunting, the Indians let them loose after mountain hares and wild foxes. And the birds, in expectation of their accustomed feed, whenever one of these animals appears, fly after it, seize it in a trice, and bring it back to their masters, as Ctesias tells us. And from the same source we learn also that in place of the meat which has hitherto been attached, the entrails of the animals they have caught provide a meal.

Aelian, On Animals, 4.26

Hares are caught by foxes more often than not through an artifice, for the fox is a master of trickery and knows many a ruse. For instance, when by night it comes upon the track of a hare and has scented the animal, it steals upon it softly and with noiseless tread, and holds its breath, and finding it in its form, attempts to seize it, supposing it to be free of fear and anxiety. But the hare is not a luxurious creature and does not sleep carefree, but directly it is aware of the fox's approach it leaps from its bed and is off. And it speeds on its way with all haste: but the fox follows in its track and continues its pursuit. And the hare after covering a great distance, under the impression that it has won and is not likely to be caught, plunges into a thicket and is glad to rest. But the fox is after it and will not allow it to remain still, but once again rouses it and stimulates it to run again. Then a second course no shorter than the first is gone through, and the hare again longs to rest, but the fox is upon it and by shaking the thicket contrives to keep it from sleeping. And again it darts out, but the fox is hard after it. But when it is driven into running course after course without intermission, and want of sleep ensues, the hare gives up and the fox overtakes it and seizes it, having caught it not indeed by speed but by length of time and by craft.

Aelian, On Animals, 13.11

The interior portion of Britain is inhabited by those of whom they say that it is handed down by tradition that they were born in the island itself: the maritime portion by those who had passed over from the country of the Belgae for the purpose of plunder and making war; almost all of whom are called by the names of those states from which being sprung they went thither, and having waged war, continued there and began to cultivate the lands. The number of the people is countless, and their buildings exceedingly numerous, for the most part very like those of the Gauls: the number of cattle is great. They use either brass or iron rings, determined at a certain weight, as their money. Tin is produced in the midland regions; in the maritime, iron; but the quantity of it is small: they employ brass, which is imported. There, as in Gaul, is timber of every description, except beech and fir. They do not regard it lawful to eat the hare, and the cock, and the goose; they, however, breed them for amusement and pleasure. The climate is more temperate than in Gaul, the colds being less severe.

Caesar, Gallic War, 5.12

Greek Anthology, 7.207

Edward Topsell, History of Four Footed Beasts, p. 210

The hare [lepus], as if the word were levipes (“swift foot”), because it runs swiftly. Whence in Greek it is called lagós, because of its swiftness, for it is a speedy animal and quite timid.

Isidore of Seville, Etymologies, 12.1.23

Lucius Aelius thought that the hare received its name lepus because of its swiftness, being levipes, nimble-foot. My own opinion is that it comes from an old Greek word, as the Aeolians called it λέπορις. The conies are so named from the fact that they have a way of making in the fields tunnels (cuniculos) in which to hide.

Varro, De Re Rustica, 3.12.6

There are a great number of hares, but they are a small breed, much resembling rabbits both in size and the softness of their fur. In short, it will be found that the bodies of all animals, wild beasts, and birds, each in its kind, are smaller here than in other countries; while the men alone retain their full dimensions. It is remarkable in these hares, that, contrary to the usual instincts of that animal, when found by the dogs, they keep to cover like foxes, running in the woods instead of in the open country, and never taking to the plains and beaten paths, unless they are driven to it. This difference in their habits is, I think, caused by the rankness of the herbage in the plains, checking their speed.

Gerald of Wales, Topographia Hibernica, 12

A hare, as he says [i.e. Liber rerum] is a very small animal. It grows rapidly. Among other animals it is the most timid, so that it rarely goes out to graze later in the night. It is never fat, as Pliny testifies. The weasel is said to play with the hare for fun. And when it sees the hare is tired of the game, it seizes its throat with its teeth and squeezes it very hard. Soon the hare, feeling the bite of the weasel, tries to escape with haste, but being burdened with the treacherous weight, even if it is able for a little while to escape death by running, its weariness prevents that escape, for the weasel follows. So it happens that having exhausted the hare, that wicked beast kills it with cunning and eats it. They change their sex every year. In the winter months they have snow for food; and this is proved by the fact that they glow behind the snow. Ambrose: In some parts of the world, hares turn white in winter, but return to their original color in summer. As the Experimentator says, the hare, in the time of sowing and reaping, rejoices and is moved to play, as if it were playing a game, because it thinks it has time in abundance, and therefore a time for pleasure, not for merit. A hare's lung is placed over its eyes. But when it is broken and anointed it heals wounded feet. Its bile brightens the eyes. Its kidneys, dried and powdered, and drunk, expel stones from the bladder. Its blood, drunk with warm water, does the same thing. Its flesh generates thick blood; but it is useful to those who have too much moisture. Its legs are longer behind, so it happens that it is easier for it to climb a mountain than to go down. It does not chew the cud. It sleeps with its eyes open. Says the great Basil, that the race of hares is not easily destroyed, wherever they begin to live, and this because they multiply beyond estimation, so that a special favor may be said of them: Grow and multiply. If a hare is fed indoors with people and lacks natural speed of movement, it grows fat on its kidneys and dies. For much movement in an animal diminishes its fat, which it would certainly have been able to gain from much food. The hare dances around the place where it should rest, with multiple bends, in order to deceive the hunters; and this can be experienced especially in the season of snow. Solinus: The hare, being born as the prey of all, had to multiply beyond measure, and in this nature was kind, since almost alone, when it gives birth to offspring, it simultaneously bears one clothed with hair in the womb, another without hair, and another stored in the seed.

Thomas of Cantimpré, Liber de Natura Rerum, Quadrupeds 4.65

Edward Topsell, History of Four Footed Beasts, p. 210