The Horrible Deliverance

Translation of Louis Pergaud's short story from De Goupil à Margot (1910)

I.

The darkness was opaque. Nothing disturbed the hum of the thaw. A sudden click of metal cut through like a swath of silence, and a howl, no longer of life, seemed to spring from the void and spill into the space like a cataract of horror bursting the gates of the night... The beast was caught...

Born of fleeting loves in the penultimate spring, Fuseline, the little marten with a grey-brown coat and snow-white throat, had, that day, as usual, come from the edge of the beech and hornbeam wood where, in the fork hollowed out by time of an old mossy pear tree, she had taken her winter quarters.

Since the snow had driven the migratory birds far away in triangular caravans, she had seen her resources diminish rapidly, and to quench her unquenchable thirst for blood, she had, like her sisters in plunder, forsaken the deserted thickets and sought towards the village her daily sustenance.

She came there every evening, more cautious or less daring than her older companions who had long since arranged retreats in the cavernous gaps of the old shingle roofs.

Those times were now distant when, with the complicity of the russet moon, she climbed the young oaks to surprise, during their sleep, the newly arrived blackbirds on their brood of nestlings: there remained in the wood only a few old residents whose never-failing wariness defied any surprise.

Through a hole in a broken pane, rudely patched with paper, through the cat flap of a door, or the gap in a low wall where the beams rest, she had managed, one night, to slip her worm-like body into a farmer's barn, and from there, falling through the hay chute into the cows' manger, to penetrate the warm stable where the chickens roosted.

Then she had lightly leaped onto the perch where they were lined up, perched on their folded legs, and had bled them to the last.

With a bite near the ear, she severed the carotid artery, and while the warm blood flowed, which she voluptuously sucked, she held the stupid creature under her sharp claws like those of a cat, leaving it, warm, drained, limp, in the final throes of agony.

Like a drunkard, disdainful of flesh after the bloody binge, mad with joy, her throat smeared, her coat sticky, her body swollen, she had returned to her wood, indifferent to the tell-tale prints of her paws.

What had happened in the brief time, though short, during which she had sobered up from her blood feast!

Now the houses had all closed up like citadels, behind whose walls growled the fierce mastiffs with powerful fangs, or where, on moonlit nights, men kept watch, emerging as giants from the embrasures of shadow to cast into the silence, with a brief red flash, the resounding thunder of a gunshot that sent all four-legged prowlers driven by hunger towards the village retreating into the distance.

The nocturnal hunts passed in fruitless and monotonous wanderings along the garden walls, through the gaps in the orchard hedges, and the slopes of wooden roofs.

How many days had this life of misery lasted? But that night, in the pale light of a star slipping between two clouds like a ray of light filtered from the threshold of an aerial cottage, she had given in to the irresistible lure of a wall breach; she had skirted a dried tangle of poles for staking peas that streaked the snow with a grey line, and at the very end, as if these half-rotten branches had been a providential index finger, she had found there, almost blending with the whiteness of the snow, a large freshly laid egg which she had eagerly gobbled up... The next day she found a similar one and so for several consecutive evenings, for every night now she returned there to seek her only sustenance. The rest of the night was spent in fruitless searches, and always the late dawns of those winter mornings found her, agile and cautious, crouched in the cavernous fork of her sylvan home.

II.

Evening had returned, an evening of thaw with a livid sky laden with heavy clouds: bundles of snow saturated with water dripped from the tall trees like the laundry of an immense wash, or crashed to the ground with the dull sound of bursting pouches; streams of water whispered everywhere; the earth seemed to be brooded over by a great mysterious wing made of warmth and rustlings, and over all this hung the anxiety of a genesis or an agony.

At the grey skylight of the cavern, the little white throat had appeared like a clump of snow silently fallen from an upper branch, and, moving slowly, Fuseline descended to the ground.

Quickly, quickly, for the day has been long and her stomach is empty, she follows the usual path she takes every evening: the pointed tips of her curved paws, with their powerful joints, barely brush the grey mud of snow and soaked earth; her long bushy tail swings lightly: she cuts through the silent paths that form darker bars in the snowy night; she skirts the enclosure walls of rough stones and the black hedges with whitish, crumbling tops, giant clepsydras from which the dying season seems to drip; the blood of hope beats stronger in the veins of the beast and her desire for the forthcoming meal grows.

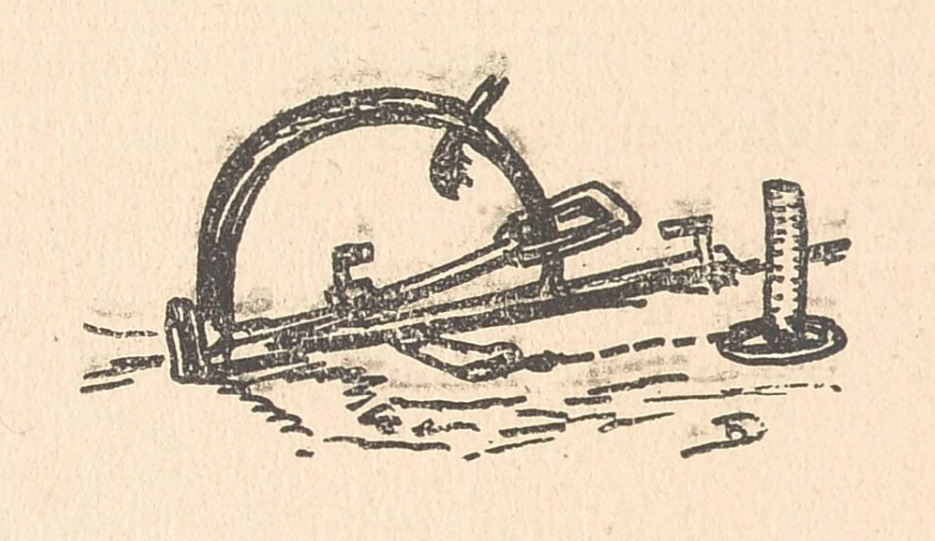

Here is the breach in the wall and the rotten branches against which, as if by accident, large beams have been placed, creating a single passage, a narrow channel to reach the egg whose whiteness tonight stands out against the earth bare of the snow from previous days. She sees it, she is sure of her meal, and something in her beats faster and stronger. Just a few more leaps and she will break the fragile shell; let's go! And she leaps when, suddenly, the impetuous arms of a trap, violently closing their embrace, have caught in their terrible grip the little adventurous paw, holding it prisoner in their formidable vice.

In the nameless pain of capture, her cry burst forth, biting into the calm night with its terror, while beside her, insidious rustlings, sudden impacts, and cracklings of wood revealed the hurried retreat of the wild animals prowling around.

The horrible pain of the broken paw, the bitten flesh, the torn skin stiffened her entire body in a convulsion of despair to escape this grip. But what can the wildest contraction of muscles do against the unyielding grip of steel springs!

In vain she tries to bite them; but her teeth recoil before the cold of the pitiless metal that would break them, and like all violent efforts that fail, the pain that incited it escapes in whimpers.

In the distance, a gunshot rings out; then she understands the trap; the man will come to finish her off, and she will be unable to flee or defend herself. And in the pain of the grip that bites her and the panic of danger, she shakes and writhes in convulsions of despair.

The trap remains there, fixed to the ground, motionless; her small head is thrown back in the stiffness of the uninjured paw that stomps the ground in rage, while the hind legs brace themselves like springs.

Her tensed loins pull backward, sideways, forward: nothing gives! nothing moves! A massive chain holds the trap’s jaw to a ring on the ground, its iron teeth making horrible bites in her flesh; drops of blood slowly trickle out and she licks them. Then, as if abandoning the struggle after the fatigue of convulsive effort, she seems to resign herself, forget herself, fall asleep from pain or exhaustion, and at times, as if whipped by a thousand lashes of suffering, she rises again, throbbing with formidable life, vibrating, leaping, howling entirely to break or loosen the grip that holds her.

But it is in vain, and time flies, and the man may come. Soon over there, behind the snowy shoulder of the mountain, dawn will break: a nearby rooster announces it with a metallic crow that awakens the oxen whose chains clink in the silence of the night.

She must flee, flee at all costs. And in a more violent jerk, the bones of her paw crack under the bite of the steel. One more effort: she throws herself to the side and the points of the broken bones pierce her skin like lances, the stump attached to her chest is almost free. All her energy condenses on this goal; her bloodshot eyes blaze like rubies, her mouth foams, her fur is bristled and dirty; but the flesh and skin still hold her like cords binding her to the murderous trap; the danger grows, the roosters respond to each other, the man is about to appear.

Then, at the peak of pain and fear, trembling under the formidable grip of instinct, she rushes at her broken paw and, with frantic bites, chops, slices, grinds, and saws the bloody, twitching flesh. It’s done! One fiber still holds: a convulsion of the loins, a snap of muscles, and she tears free like a bloody thread.

The man will not have her.

And Fuseline, without even looking back in a final farewell at her frayed and red stump left behind, to attest to her invincible love of space and life, drunk with suffering but free nonetheless, plunged into the mist.